According to the latest statistical data, the Canadian recession ended sometime over the summer and we will see slow growth in the third and fourth quarters of 2009. While this is likely to be a jobless recovery until sometime in 2010, Canadians believe that our conservative banking culture coupled with greater financial market regulation spared us the mortgage melt-down and destruction of consumer wealth that devastated other first world economies. While that may be the case, it does not mean that Canada is perfect on all major economic and government policy issues. This article takes a look at some major issues facing western economies and what international organizations like the World Bank have to say about Canada’s success in managing them.

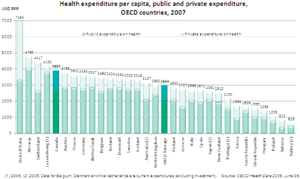

Canadian health care is not quite the model that everyone wants to emulate. As the debate over Obamacare rages in the United States, one of the rare points on which Democrats and Republicans agree is that they do not want the Canadian-style single-payer option, where the government pays the bills, makes treatment policy and private insurance is a minor tack-on for those who receive it through their employers. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Canadian governments are responsible for 70% of all health care spending in the country, which is slightly below the OECD average of 73%. Overall, Canada spends 10.1% of GDP on health care, far below the United States at 16% but still above the OECD average of 8.9%. Our spending per capita is more generous that most, as evidenced by the table below.

All is not wonderful in Canadian health care, however. Canada has far fewer physicians per 1000 people, standing at 2.2 versus 3.1 for the OECD. We are behind in nurses per thousand at 9.1 versus 9.6 in the OECD overall, but where we really fall behind is in the availability of sophisticated diagnostic equipment. We have 6.7 MRI machines per million in population against 11 in the OECD, and for CT machines, the ratio per million is 12.7 against 20.2 – we are far behind in making equipment available that is critical for early diagnosis and testing. The message for Canada is that while we may have access to government health care and spend more than most of our OECD associates we are not investing fast enough in the latest technology and our stock of doctors is insufficient to allow everyone access to a family physician, for instance. Given that Canada has an aging population that is not going to be rejuvenated by massive waves of immigration as it was in the early 20th century, we have to keep our population healthy and working longer. Aging boomers facing a health care gap as evidenced in the OECD study should either be prepared to pay for private diagnostic treatment or stand in ever-increasing lineups as demand on the public system becomes overloaded.

The message for Canada is that while we may have access to government health care and spend more than most of our OECD associates we are not investing fast enough in the latest technology and our stock of doctors is insufficient to allow everyone access to a family physician, for instance. Given that Canada has an aging population that is not going to be rejuvenated by massive waves of immigration as it was in the early 20th century, we have to keep our population healthy and working longer. Aging boomers facing a health care gap as evidenced in the OECD study should either be prepared to pay for private diagnostic treatment or stand in ever-increasing lineups as demand on the public system becomes overloaded.

When it comes to trade and investment policy, the OECD correctly fingers Canada as a major hypocrite among OECD nations. We ask for free trade with our US neighbor and cry about the Buy American provisions of the US stimulus package, but we protect our own provincial and municipal procurement system from US suppliers. The federal government is trying to work out a deal with the provinces on this issue, but progress is slow. There are over 100 trades and 50 professions that are covered by provincial regulation in Canada, which means that Canada does not have a mobile labour market and this creates financial and employment distortions across the country. Jean Charest is working to create a common labour market with France, and if he is successful a plumber from Lyon will have an easier time getting accredited in Quebec than one from Belleville, Ontario.

The OECD points out that Canada has significant restrictions on foreign direct investment in the telecommunications, transportation and broadcasting sectors and this hampers modernization, international competitiveness and creates higher structural costs for consumers – there is a price we are all paying for protecting the “Canadian” players in these industries. Canada’s own Competition Policy Review Panel tabled a report in 2008 that recommended liberalizing restrictions in these areas but the government has been reluctant to act and cherry-picked a few suggestions to make it look like we are making progress, like now the Minister responsible for the economic sector has to justify why an investment should not go through. This is instead of forcing the investor to demonstrate why it should go through – this is what passes for freer markets in Canadian investment policy.

Our banking sector comes across as a star, according to a July 2009 report by the International Monetary Fund. The IMF compared Canadian banks to a large basket of US, British, Swiss, Japanese and other international banks and determined that it was the conservative lending policies, capital funding from retail client deposits (which are more stable than wholesale funding models) and higher balance sheet liquidity that allowed our banks to withstand the financial tsunami. Our banks were less leveraged, the retail client was a stable depositor and our sane mortgage model avoided the massive erosions of capital that plagued the US and British banks. Ironically, prior to the crisis our banks were not the best capitalized on the list, landing in the third quartile; however our banks lost far less of their capital during the crisis than their international peers, many of whom saw capital declines of 70 to 85 percent and ran into the arms of government for relief funding.

The IMF report highlights that Canadian banks were exemplary in their limited exposure to troubled U.S. assets. While many international banks snapped up U.S. mortgage-backed securities because of their high rates of return (supposedly) the Canadian banks held their mortgages rather than packaged and traded them, so they had less liquidity for investment in riskier vehicles and had the incentive to make sure that the loans they were making were of high quality. Canada’s regulatory environment also has more stringent capital requirements that gave our banks a more stable equity base when the capital markets started to slide.

The great irony is that what saved our banks over the past two years is exactly what our banks used to be criticized for; too stodgy, focused at home, and too small to compete effectively in international capital markets for big deals. Going forward, if the US re-regulates the banking industry to look like what it did at the end of the 1970s then the American banks are likely to look and behave a lot more like Canadian ones. If US banks re-trench in this way, then perhaps the Chinese and Indian banks will be the big risk-takers in the next wave of international finance.

Readers already know that Canada’s national debt and annual federal deficit are lower than those of the European Community and substantially below the US deficit for fiscal 2009, estimated at 10% of GDP. The corresponding figure for Canada is estimated at 3% of GDP, which even at $50 billion is still far less on a percentage basis than most of the deficits of the 1980s.

Politicians are often counseled not to waste a good crisis, and this one offers many opportunities to fix longstanding structural problems in Canadian economic policy because we are in a stronger position than most of our OECD competitors. Canada had better shape us fast, though, because our true challengers of the 21st century are China and India, not the US and Europe. The sooner we learn how to position ourselves to trade with these two giants the better, and we can learn to do so while our old-world competitors are still digging themselves out of a far deeper hole than ours.