In 1976, French President Valery Giscard d’Estaing decided that it would be a good idea to invite the leaders of the major western economic powers (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States of America) to an informal summit at a chateau outside of Paris to discuss their current common economic problems, giving birth to the G7. Later expanded to include Russia (G8) this intimate grouping of world powers dominated the international economic and trade agenda until the Asian currency crisis of 1997 had ripple effects around the world, making a broader consultative forum a priority to encourage cooperation with the developing world. That body was christened the G20, and today it represents nearly 85% of worldwide economic output (GDP) though 90% of the world’s countries are not at the table.

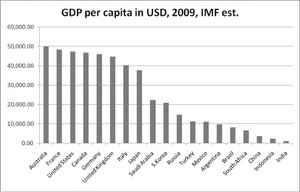

While the big GDP players are well known to be the original G7 plus China, it is more useful to look at economic output on a per capita basis, displayed graphically.

Though Canada may have a smaller total GDP than the original G7, we are near the top of the list on a per capita basis and are way ahead of upcoming Asian powerhouses like China and India. Canada is no longer the small player at a table of seven, but a serious contender for power and influence in a broader economic forum. Canada is also hosting the 2010 meeting in Hunstville, Ontario. What does Canada intend to do with its newfound clout? Does our government have a set of objectives and a strategy to achieve them? The following paragraphs detail a few positions worth considering as we move towards Hunstville 2010.

On trade, Harper has been a consistent promoter of free and open markets and has encouraged other world leaders to resist the domestic pressure to return to protectionism for short-term political gain. Canada will find a strong alliance, if it seeks one, with China and India who need to keep overseas markets open if they are to continue to grow their economies. While India and China’s need to export is obvious, they also need to maintain access to technology developed abroad as they build their own high-tech sectors. Another important consideration is continued immigration to western nations so their young people can attend the finest universities available and bring their knowledge back home for dissemination and the creation of economic value.

On trade, Harper has been a consistent promoter of free and open markets and has encouraged other world leaders to resist the domestic pressure to return to protectionism for short-term political gain. Canada will find a strong alliance, if it seeks one, with China and India who need to keep overseas markets open if they are to continue to grow their economies. While India and China’s need to export is obvious, they also need to maintain access to technology developed abroad as they build their own high-tech sectors. Another important consideration is continued immigration to western nations so their young people can attend the finest universities available and bring their knowledge back home for dissemination and the creation of economic value.

What should Canada ask of these nations in return? From China, Canada should ask that the government be less aggressive in encouraging its natural resource companies from buying up Canadian mines and development companies, regardless of how tempting those targets may be. Rather than buying up assets here, the Chinese should be directed towards seeking joint ventures with Canadian companies in China to further the development of that country’s under-exploited natural resource sector. While foreign companies already invest heavily in the Chinese natural resource sector, Canada can offer special expertise for operating under difficult geographical or weather conditions, more so than the Americans and Europeans. Canada can avoid an anti-foreign investor backlash at home and expand our reach abroad at the same time.

Looking further at natural resources, Canada has what the world wants: energy and water. We have renewable freshwater resouces which the Americans are desperate to share, and oil and gas that the whole world still needs even as we seek alternatives to a carbon-combustion economy. The current problem is that Canada consumes enourmous amounts of water to facilitate oilsands extraction, up to 10 barrels of water for one barrel of oil. Even though a great deal of this water is recycled, the political optics look bad at home and worse abroad as American environmentalists and Europeans (across the board) scold us for using copious amounts of one resource to extract another.

Canada should use its influence to quiet these voices, and remind them that if they want oil from a politically stable ally then they should stop criticizing the trough from which they feed. If the US, the European Union and even the Chinese wish to gamble their economies on the long-term viability of Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Iraq, so be it – Canada can seek clients elsewhere if their attacks continue to remain so shrill and incessant in nature.

The environmental issue is coming to a head in Copenhagen where world economies are seeking a replacment for the failed Kyoto round of emissions caps. Copenhagen is looking less like the reductions sought by Kyoto and more like a transfer of trillions of dollars from the developed to the developing world as compensation for future first world pollution. The Copenhagen round is a complete, untenable, nonsensical farce because none of the developed world’s economies can afford these transfer payments and the developing producers like China and India have no plans to divert funds from building their economies to the corrupt regimes of central Africa, for instance. If Canada really wants to assert leadership at the G20, then it should stand up now and declare that the Copenhagen round is a non-starter and pull out. Canada can, and will stick to it’s own plan for acheivable targets and the rest of the world should buy in as long as other nations want to consume what we extract from the earth.

A final consideration must be given to currencies and the talk of replacing the USD as the world’s reserve currency by a basket of the Euro, the Yuan and a smattering of others. Canada’s major trading partner remains the United States and any move away from the USD will impose increasingly complex transaction costs on Canadians as we would have to learn to quote and purchase in a new world currency that could end up being more unstable than the one it seeks to replace. It is not the first time that other countries have talked about replacing the US Dollar, but the discussion has more traction this time as the US monetizes its current deficit and future inflation would devalue the US national debt held by other nations, notably China. Canada should, in its own interests, forcefully denounce this movement and express confidence in the USD and encourage other nations to discard this distraction and work on more productive issues, like international banking regulation reform.

Canada has a fantastic position within the G20 of being in better economic shape than most and producing what the world wants. It is now up to our government to capitalize on our enviable status and advance our agenda in a way that demonstrates that our interests represent clear, realistic and coherent policies for other G20 members to emulate.