A US president comes to power promising a change in foreign policy after the previous administration is discredited by overseas wars and tensions among its allies. A recent world financial crisis, coupled with increased spending on social programs has strained government spending. Upon entering office, the new president increases US military iniiatives in the hope of bringing a swift end to the fighting. Almost two years into his mandate, the mid-term elections loom and the president is facing important losses in both the House and Senate, threatening his administration’s ability to pursue its agenda. A presidency that began with so much promise has delivered little success abroad and at home, and fears the results coming in November.

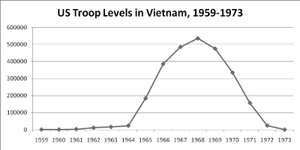

Readers would be forgiven for believing that this is about Obama in 2010. Surprisingly, this is exactly the scenario that Richard Nixon faced in late 1970, two years after the first presidential election. Here’s a brief history primer; in 1968 Nixon campaigned for the presidency based on his commitment to chart a new course in Viet Nam and to extricate the US from a war that Americans did not understand from a strategic point to view and were fatigued by as a nation from watching their sons die in an endless war. The Johnson administration, which placed over half a million troops in Viet Nam, was unable to negotiate a truce with the Viet Cong regardless of never losing a battle on the ground. Nixon escalated the war with the secret bombing of Cambodia, where the Viet Cong had bases in the same way that the Taliban operate in neighboring Pakistan today. On the economic front, Nixon came to office after the currency crisis of 1968, in which the French moved to decouple their currency from the US Dollar and gold, representing the beginning of the end for the Bretton Woods gold standard agreement that had produced 20 years of international currency stability and low inflation in the aftermath of WWII. Internally, the US government was just starting to pay for Johnson’s Great Society and civil rights package of social programs that had divided the country at the outset and raised great opposition from many conservative Americans, in the same way that Obama’s bailouts and national health care plans affected the current political terrain. Twenty months into both the Nixon and Obama administrations, the public was frustrated and ready to vote for the other party to punish the incumbent in the executive office.

Readers would be forgiven for believing that this is about Obama in 2010. Surprisingly, this is exactly the scenario that Richard Nixon faced in late 1970, two years after the first presidential election. Here’s a brief history primer; in 1968 Nixon campaigned for the presidency based on his commitment to chart a new course in Viet Nam and to extricate the US from a war that Americans did not understand from a strategic point to view and were fatigued by as a nation from watching their sons die in an endless war. The Johnson administration, which placed over half a million troops in Viet Nam, was unable to negotiate a truce with the Viet Cong regardless of never losing a battle on the ground. Nixon escalated the war with the secret bombing of Cambodia, where the Viet Cong had bases in the same way that the Taliban operate in neighboring Pakistan today. On the economic front, Nixon came to office after the currency crisis of 1968, in which the French moved to decouple their currency from the US Dollar and gold, representing the beginning of the end for the Bretton Woods gold standard agreement that had produced 20 years of international currency stability and low inflation in the aftermath of WWII. Internally, the US government was just starting to pay for Johnson’s Great Society and civil rights package of social programs that had divided the country at the outset and raised great opposition from many conservative Americans, in the same way that Obama’s bailouts and national health care plans affected the current political terrain. Twenty months into both the Nixon and Obama administrations, the public was frustrated and ready to vote for the other party to punish the incumbent in the executive office.

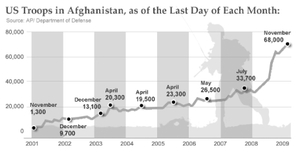

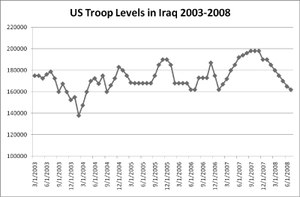

The US suffered through another year of war before US troops began their withdrawal in 1973. The Nixon administration’s policy was to reduce troop commitments while building up domestic military forces to allow the Vietnamese to fight their own war – they called it “Vietnamization”. Obama has been pursuing a Vietnamization policy of his own – which may eventually work out in Iraq, since the Iraqi theatre of operations is a more mature war and the insurgency is practically over, while Iraqi troops will still benefit from 50,000 US service personnel to act as advisors in order to complete the mission. In Afghanistan, Vietnamization is going poorly, and there is no belief that Afghani troops will be able to assert control of the country if the US leaves as planned before the end of Obama’s term. By mid-1972, American troop strength in Vietnam had been cut nearly in half to approximately 260,000, which is more or less equivalent to Obama’s troop reduction in Iraq (100,000 to 50,000) during his tenure. In both cases, the reductions were not enough to placate the voting public into believing that the end was near, especially as troop strength in Afghanistan is now up to 90,000 or more – the troops have been shifted, the theatre of operations representing the most intense fighting has merely changed scenery.

The US suffered through another year of war before US troops began their withdrawal in 1973. The Nixon administration’s policy was to reduce troop commitments while building up domestic military forces to allow the Vietnamese to fight their own war – they called it “Vietnamization”. Obama has been pursuing a Vietnamization policy of his own – which may eventually work out in Iraq, since the Iraqi theatre of operations is a more mature war and the insurgency is practically over, while Iraqi troops will still benefit from 50,000 US service personnel to act as advisors in order to complete the mission. In Afghanistan, Vietnamization is going poorly, and there is no belief that Afghani troops will be able to assert control of the country if the US leaves as planned before the end of Obama’s term. By mid-1972, American troop strength in Vietnam had been cut nearly in half to approximately 260,000, which is more or less equivalent to Obama’s troop reduction in Iraq (100,000 to 50,000) during his tenure. In both cases, the reductions were not enough to placate the voting public into believing that the end was near, especially as troop strength in Afghanistan is now up to 90,000 or more – the troops have been shifted, the theatre of operations representing the most intense fighting has merely changed scenery.

The two troop graphs covering Iraq demonstrate that while the Bush administration began removing troops from Iraq following the surge in 2007, the increase in Afghanistan began as soon as Obama took office. When poliical pundits refer to Afghanistan as “Obama’s war”, they mean that Obama has made it his war of choice, that this is where the money will be spent and Obama’s reputation will succeed or fail.

The two troop graphs covering Iraq demonstrate that while the Bush administration began removing troops from Iraq following the surge in 2007, the increase in Afghanistan began as soon as Obama took office. When poliical pundits refer to Afghanistan as “Obama’s war”, they mean that Obama has made it his war of choice, that this is where the money will be spent and Obama’s reputation will succeed or fail.

The third graph shows the rapid removal of US troops from Vietnam by Nixon following his election, up to the Paris peace talks of 1973. Nixon did not have another war underway, and his normalizaton of relations with China was an effort, in part, to get the Chinese not to step in to overtly aid the Viet Cong while the US pulled out.

While the similarities of the political situations Nixon and Obama faced in their overseas wars is remarkable, the economics of each situation are completely different. Obama inherits an economy at the end of a spend and borrow frenzy that has impoverished governments and their citizenry, while Nixon was one of the principal architects of its unleashing. Following the French decision to decouple the Franc from the US Dollar and gold, other nations saw this move as the means to abandon fiscal conservatism and move to inflate the money supply since the nations’ gold reserves would not have to increase in proportion to the money in circulation. This allowed countries to either borrow massively to fund the social program initiatives of the 1960s, expand the money supply available to government via their central banks, or in most cases, do both. When Nixon formally abandoned the gold standard in 1973, he made the famous remark, “we are all Keynesians now” indicating that massive government spending, stimulus and deficit were considered to be mainstream economic doctrine. Inflation quickly followed the unleashing of fiscal and monetary expansion in rapid order – it was Gerald Ford, as president in 1975, who had to initiate an inflation control program called “WIN”, Whip Inflation Now. It did not work, and the US waited until Paul Volcker and his 22% interest rates in 1979-80 brought inflation back down, just in time for the deficits of the Regan era.

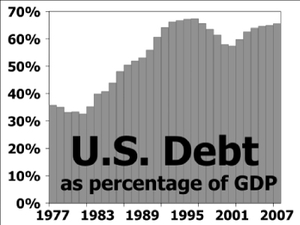

No one stopped deficit spending in the US for the next 35 years – Democrat or Republican, except for a couple of years at the end of the Clinton era. With the US federal debt nearing 12 trillion and climbing, the US can no longer afford either guns or butter – which President Johnson famously indicated as both being possible in 1965.

No one stopped deficit spending in the US for the next 35 years – Democrat or Republican, except for a couple of years at the end of the Clinton era. With the US federal debt nearing 12 trillion and climbing, the US can no longer afford either guns or butter – which President Johnson famously indicated as both being possible in 1965.

The Vietnam war cost somewhere between $110 and $130 billion US in non-inflation adjusted dollars, while the total for Iraq and Afghanistan is not yet known, but it will certainly exceed $1 trillion USD. When the US was paying for Vietnam, it was an unrivaled economic superpower that was producing wealth in far greater quantities than it was indebting itself and it was just at the start of the debt cycle. Now, the US has multiple economic rivals with whom it must compete in a vastly expanded trading environment and its productivity is no longer creating increases in wealth to adequately support its accumulated debt.

Source: Budget of the United States Government for the Fiscal Year 2009

When Barack Obama took power in 2009, the US debt as a percentage of GDP sat at 83.4%. You can see that even after the Vietnam War, the US debt began falling as a percentage of GDP because the US was still able to grow its economy more quickly than its debt. The Reagan era of tax cuts set Americans on an anti-tax agenda that exists to this day; the peace dividend that the Clinton years benefitted from after the fall of the Soviet Union was not to last, as military spending for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan coupled with further tax reductions during the second Bush era were never matched by spending restraint in other sectors of US federal spending.

The US will eventually extricate itself from Iraq and Afghanistan, though it remains to be seen if Afghanistan will be able to avoid becoming a failed state governed by tribal leaders and fanatical religious zealots. No matter what the geopoliical outcome, the US will be financially exhausted without an obvious strategy to unleash a new era of economic prosperity like the one following WWII which allowed the US to work off a debt level that reached 120% of GDP by the end of that war. Should the Republicans retake the US House of Representatives or the Senate this November, they will be disappointed to discover that solving the budget problems unleashed over the past decade will be both fiscally and poliically painful. By taking on these challenges, they will provide Obama with a platform to campaign against Congress as he runs for re-election in 2012 and get them to share in the blame and responsibility for bankrolling the wars overseas, and for managing their outcome.