Joe Oliver probably never imagined that his first budget would be delivered late and under the dual pressures of an election campaign on the horizon and falling revenues from oil royalties as a serious constraint on spending promises. Without the sudden passing of Minister Flaherty in 2014, Oliver would have been an unlikely candidate for the job of finance minister at all.. He came to electoral politics late in life after a long career in business and finance, arguably well equipped to handle the job – it’s just that the government’s front bench is mostly under 55 and it is rare that a 70 year-old gets the most critical economic portfolio at the cabinet table. Though his delivery is wooden at times, he has the gravitas for the job and commands respect wherever he goes. The Conservatives appreciate this kind of credibility as they seek to defend themselves against Liberal and NDP accusations that the government has the wrong economic priorities and is insensitive to the plight of the middle class.

The budget promises future tax rate reductions for small business and offers targeted tax incentives for families along with a new $10,000 TFSA (Tax Free Savings Account) annual contribution cap. Increasingly, the TFSA is being exploited by taxpayers with incomes below $80,000 per year, solidly middle-class territory. Many taxpayers are beginning to understand that if they create massive savings in their RRSPs, they may end up making withdrawals at higher marginal tax rates than those they would have been subjected to in the taxation year of the contribution, and also face claw-backs on their old-age security payments. Not the result the RRSP was designed to deliver – alternatively, once the money is invested in a TFSA it grows and is withdrawn tax-free, a far better deal for many

What this budget avoids is picking winners – that is, create spending programs that target specific economic groups with the notion that injecting government money is going to spur economic activity. Instead, it seeks to reduce taxation to encourage investment and job creation. This budget’s tax reductions are aimed at small business, which represents 99 per cent of all businesses in the country and employs half of all Canadians working in the private sector.

The most important measure announced in the budget may go unnoticed by many – a new plan to adjust Employment Insurance (EI) premiums to a realistic rate required to fund the program. Excess contributions will be rebated to employers and employees alike in the form of lower premiums going forward under a new seven-year break-even EI premium rate setting mechanism. This is a huge departure from the behavior of past governments under Chretien and Martin, who used massive over-contributions to the EI program to reduce the deficit. Essentially, these governments used EI premiums as a subversive tax that unfairly targeted employers and employees alike and put a damper on job creation. This EI financing reform is a very significant long-term item in the budget and deserves more prominent coverage in the media.

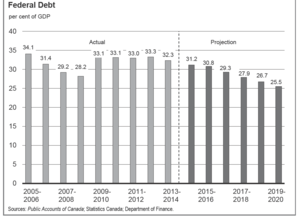

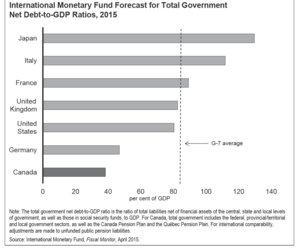

So what got the most media attention? How about the reduction in the contingency fund from $3 billion to $1 billion in order to allow Oliver to post a small surplus? Really, in an economy as large and as diverse as Canada’s, having a tiny deficit or an even tinier surplus from one year to the next is not fiscally significant, as long as the budget is near equilibrium. What matters most are the long term trends that contribute to prosperity – lower tax rates to encourage investment, spending controls that bring overall increases in-line with revenues and inflation, and a resistance to the temptation to meddle with the economy though the heavy hand of government intervention. All these positive elements have been present since the brief spending spree of the post Great Recession budget of 2009, in which Canada spent $30 billion of stimulus only to find that it was private sector investment that actually re-ignited the economy. These elements are now so entrenched in Canadian budget-making that neither the Liberals nor the NDP have any intention of going back to the interventionist policies of the 1970s and early 1980s, which may explain why they have such a hard time presenting economic plans that differ markedly from those of the Conservatives. Responsible governments lead to a declining debt burden, and Canada already has the lowest debt to GDP ratio of all the G7 nations. Canada is also planning to continue to reduce its debt ratio to 25.5% by 2019-20 – that represents real progress and creates a sustainable debt load for future generations.

It is too early to tell if this budget is the key element that will produce a Conservative victory in October – politics in Canada is too fluid to predict with certainty when we are six months out. However, the budget targets the right voter demographics and sustains the sound economic principles that have made Canada the envy of our first world partners, and that is good enough as the core of a campaign speech. Now the debate begins and the Liberals and NDP have to craft a compelling alternative to the Tories’ fiscal doctrine.

Commentaires

Veuillez vous connecter pour poster des commentaires.