Decades ago, Konrad Adenauer spoke of Germany’s postwar place in Europe when he said, “A European Germany, not a German Europe.” Since Adenauer uttered those words, Germany, together with France have been at the core of all the great initiatives to create greater European integration and cooperation – the formation of the EU, the opening up to former Eastern Bloc nations, and the adoption of the Euro. Now that the EU is in crisis over debt, deficits and currency devaluation, Germany has chosen to assert greater leadership in its own interests, effectively vetoing repeated calls to have theEuropean Central Bank act as a bank of last resort and buy up Greek, Italian and Spanish debt (as a start).

The greatest problem within Europe is the vast chasm of wealth creation between the powerful economies of the north, like Germany, and the spendthrift nations in the south, like Greece. What the Greeks could not purchase via internal wealth creation they financed through the issuance of debt, much of which was purchased by financial institutions in northern Europe. These debts were accepted as investment grade because they were denominated in Euros and the general market perception was that the wealthiest Euro members would never allow the Euro to falter. The Euro was never going to be as secure a currency as the Deutschmark was or even as the German Bund is today, but it was certainly going to be almost as solid as the US Dollar.

No nation believed in the solidity of the Euro more than Germany. It was the pledge of conservative management of the Euro (made by Helmut Kohl, Chancellor at the time) that sold the German population on the Euro and allowed the project to go forward. Germans today maintain their conservatism towards the currency and prefer its stability over the opportunistic calls from debtor nations to allow the ECB to buy up debt and print money, essentially as the Federal Reserve has done in the United States.

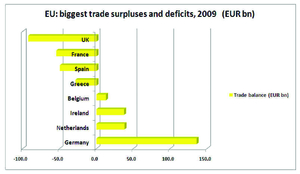

Germany also enjoys significant trade surpluses with the weaker members of the EU. Germans wish to maintain those trade surpluses because they generate wealth for the nation, sustaining employment and both personal and government revenues. The problem for the debtor nations is that they eventually need to generate surpluses within the EU in order to be able to repay their debts. The paradox is clear: Germany and other creditor nations of the EU must allow their trade surpluses to shrink or even turn into deficits in order to enable the weaker nations to build up surpluses for debt repayment. The longer the Germans resist a rebalancing of intra-European trade imbalances, the worse the problem will get. The alternative to a normalization of these trade balances is the forgiveness of the weaker nations’ debts, similar to the proposed write-off of 70% of Greece’s privately-held debt that was announced at the end of January. Either the wealthy nations of the EU curb their future net trade inflows, or their banks take the hit. Behind all the cacophony of debate over how to solve the crisis this is a basic pillar of its resolution.

Germany also enjoys significant trade surpluses with the weaker members of the EU. Germans wish to maintain those trade surpluses because they generate wealth for the nation, sustaining employment and both personal and government revenues. The problem for the debtor nations is that they eventually need to generate surpluses within the EU in order to be able to repay their debts. The paradox is clear: Germany and other creditor nations of the EU must allow their trade surpluses to shrink or even turn into deficits in order to enable the weaker nations to build up surpluses for debt repayment. The longer the Germans resist a rebalancing of intra-European trade imbalances, the worse the problem will get. The alternative to a normalization of these trade balances is the forgiveness of the weaker nations’ debts, similar to the proposed write-off of 70% of Greece’s privately-held debt that was announced at the end of January. Either the wealthy nations of the EU curb their future net trade inflows, or their banks take the hit. Behind all the cacophony of debate over how to solve the crisis this is a basic pillar of its resolution.

This is not the first time that the trade imbalance analysis was used to predict a future currency reversal. Back in the early 1980s when the Reagan deficits topped $200 billion per year, economists argued that the USD would have to fall against the currencies of its trading partners in order to generate the net cash inflows to repay the federal debts contracted with foreigners. This situation never came to pass because foreign investors in US debt were content to purchase even greater amounts over time since the USD was the world’s reserve currency. Also, US debt as a percentage of GDP was far lower in the early 1980s than it is today. Europe will not enjoy the same kind of “free pass” that the US enjoyed 30 years ago. Firstly, because overall debt levels in Europe are far higher than those of the US, either today or in the past. Secondly, the Euro is not the world’s reserve currency. The US currency has declined in value since 2000 against a basket of foreign currencies and as a result, US manufacturing is enjoying a resurgence and has been a leading job creator over the past 2 years. The Euro trade imbalances are intra-European so a devaluation of the Euro benefits the same large exporters of sophisticated manufactured goods like Germany, but does relatively little to solve Greece’s problems.

Germans already believe that they have made great sacrifices for the cause of European integration. If Angela Merkel were to announce to the Bundestag that she was going to take steps to reduce Germany’s trade surpluses or, in the alternative, give in to calls for the ECB to become a “bad bank” and start buying debt, she would lose her governing coalition. Telling Germans the truth is a one-way ticket out of power. The socialist opposition is probably more favorable to an ECB-led solution, but could not get elected if they proposed it. Therefore, all German political parties are wedged in by their avoidance of the unspeakable solution.

Germany will continue to favor austerity programs for the debtor nations coupled with debt write-offs and restructuring, even though it will mean that German and French banks will have to seek recapitalization from the markets or even seek mergers or bankruptcy. This policy will deepen and prolong the coming European recession of 2012 and, ironically, will lead to a reduction in German trade surpluses because their southern consumers will have far less disposable income. Therefore, the Germans are going to see their trade surpluses evaporate either due to a European recession or through deliberate policy initiatives. The policy initiatives are politically unpalatable, so German intransigence will prolong the suffering of the entire Eurozone.

The Euro requires a new political structure that will impose strict financial controls on spendthrift governments that will prevent the debt excesses that exist today from reappearing in the future once the current mess gets sorted out. Who will be at the helm of this new structure? Why, the Germans, of course! Prepare for the Euro II and a German Europe, at least in the financial sense.

Comments

Please login to post comments.