In the aftermath of the Quebec election, taxpayers wait with clenched teeth for a coherent taxation strategy to make up for the lost revenue from the cancellation of the tuition hikes, the abolition of the health care tax for some (with an increase for others) and the cost of the PQ’s election promises.

Looming large over Mme. Marois and Nicolas Marceau, her finance minister, is the increased scrutiny that any separatist government faces when it comes to the annual deficit and the Quebec debt. It has been the practice of the financial markets to put greater pressure on PQ governments to deliver good financial management than their Liberal equivalents since the threat of sovereignty would increase the required yield on Quebec debt. As long as Liberal governments were cooperating with Ottawa, there was no threat that Quebec would go it alone and there was implied support from their federal partners. If Quebec were to seek to acquire further powers in an effort to distance itself from Ottawa’s intrusions, then the corollary would be that it would also withdraw from the fed’s support as well, most notably concerning transfer payments. Quebec cannot move out of its parent’s house and still expect the old homestead to help it make ends meet at the end of the month – the other provinces would have nothing of it. The question Quebeckers need to ask themselves at the outset of this government’s mandate is whether or not, based on historical and current activities, the PQ government can be expected to deliver sane financial management within which investment and employment can continue to grow.

If readers were to base their conclusions on the improvisation of their first five weeks in power, the answer would be no. However, in the past week it is clear that the top civil servants in the finance department have explained to the government that their plans to kill the health care tax and their intention to raise the effective tax rate on capital gains and dividends are non-starters. Observers should note that the government is now moving into a rationalization phase, the euphoria of the election victory is over and the reality of meeting the National Assembly as a minority government is setting in. Mme.Marois does not wish to face another election within the first year of her mandate, and having a taxpayer and corporate revolt would embolden the opposition parties to bring down the government over its first budget, expected in April 2013. So, with a renewed commitment to continue the deficit reduction process undertaken by the Liberals, expect very few surprises over the coming session when it comes to economic policy – the fight will focus instead on language and culture, most certainly to satisfy the party’s hardliners and to demonstrate that at least they will attempt to legislate that portion of their election promises.

The table compiled by Sebastien Lavoie looks at the net public debt of Quebec since 1975, right before the election of the first PQ government under Levesque. Note that this is the net debt, which deducts the approximately $60 billion that is considered to be “investment” in Quebec infrastructure and corporations, and is not the product of deficit spending for yearly, recurring items. Quebec adopted this new accounting policy in 1998 to essentially take money off the books, simply saying that if we spend $100 million on a bridge, it counts as an investment and not as expenditure for annual deficit purposes. If this sounds like cooking the books to you, you would be right – but when you are the government you can make up your own rules, so let’s just avoid ten thousand words of explanation and go with the analysis at hand for now.

The overall picture is that regardless of government, the debt just kept on growing. Under Levesque (1976-1985) the debt ballooned from practically nothing (a few $billion) to approximately $35 billion. Now, during the late 1970’s, all the Western economies were dealing with the aftermath of the oil shock and stagflation (inflation and unemployment) that ramped up spending on the social programs that were adopted during the 1960’s. Yes, the PQ’s performance was terrible, but everyone was doing it and debt levels against GDP were relatively low, so no one really cared. This problem was for future generations to deal with at that point.

The Liberals return from 1985 to 1993 and ride a wave of relative prosperity generated by the Reagan revolution to the south, our surging exports under Free Trade adding to Quebec’s coffers. The debt kept rising, just more slowly – about $20 billion of debt was added under Bourassa II’s (and a little Daniel Johnson) tenure. Now, Nixon told us in 1973 that “we were all Keynesians now” so Bourassa, that economics whiz-kid, should have generated surpluses that would have reduced the debt. That has hardly been the case – Quebec continued to run deficits all through this time.

The Parizeau-Bouchard-Landry era brought us two significant economic events – first,the zero deficit crusade of Lucien Bouchard in the post-1995 referendum era that actually generated event number two - one real year of a balanced budget, 1998-99, with a slightsurplus of $126 million. That was the first and only time over 40 years that the budget was balanced. Recall that this was after the rule change that took expenses considered as investments off the books.

The Charest Liberals came to power with a plan to re-make government in Quebec and slaughter its sacred cows – and the cows won. During Mr. Charest’s tenure the net debt rose by another $45 billion and if you were to use the old accounting method, that number is more like $60 billion. When Mme. Marois accused M. Charest of adding 50% to Quebec’s debt during his time in office, she was absolutely correct – and when Mr. Charest answered that he was forced to invest in Quebec’s infrastructure that had been neglected for 30 years, he was right as well. His defense was that his debt was “investment” under the PQ’s law and should not be treated as current deficit expenditures.

So, the conclusion is that regardless of who was in power over the past 40 years, the debt continued to grow through good economic times or bad, federalist or separatist governments, cooperative with Ottawa or not. We have grown government in Quebec without creating a base of new wealth to fund its sustainability. The incoming government is confusing wealth transfer with wealth creation through growth, and is forgetting that human and financial capital is increasingly mobile. The great irony for Mme. Marois will be that to create a Quebec economy that can stand on its own outside of the Canadian cocoon it will have to create one of the most pro-business environments in the Western Hemisphere in order to do so. The socialist side of the PQ is unlikely to let this happen, and the PQ government is going to have a hard time retaining talent here, raising taxes from new growth, and its revenue projections will fall short as a result.

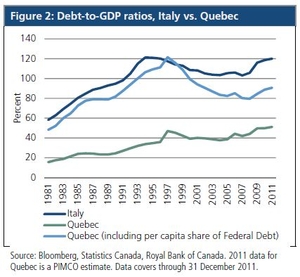

Why does any of this really matter? Look at the PIMCO analysis below that compares the Italian debt situation to Quebec’s. The PIMCO study indicates that Quebec’s debt as a sovereign nation (assuming that it accepts its share of the federal debt) would be close to the Italian levels that caused Italy to lose the confidence of international investors and face unsustainable 7% yields on its national debt. Quebec is shielded from this scrutiny as a member of the Canadian federation and benefits from the sound financial management of the central government. Were Quebec outside the Canadian Federation, investors would impose the same scrutiny on Quebec as they did to the PIIGS of Europe (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) and would likely demand similar interest rates of the new Republic of Quebec. Quebec would be unable to sustain the interest payments on such a high debt level – why do you think separatists argue that they are not “obliged” to accept their full portion of the federal debt? It would cripple the new nation and force it to seek the same recourse to the IMF as some of the European debtor nations. The Europeans have a troika helping them out – The IMF, The European Central Bank, and the European Union – where are the other two members of Quebec’s troika? Are Canada and the US going to ride to Quebec’s salvation? Not very likely.

If you are a federalist, there is a silver lining to Quebec’s massive debt. The conclusion to the analysis above is that Quebec is ill-equipped financially to go it alone anytime soon. It would take a decade or more of restraint and reform for Quebec to get its debt to GDP ratio down to a level that a new nation could support. The nastiest revelation for Mme. Marois is that her predecessors, whether separatist or federalist, have made her dream far tougher to realize than her supporters imagined.

Comments

Please login to post comments.