During a break in a conference I attended recently I was asked by several pundits what I think about – what has been erroneously named – the “Arab Spring”, and whether the populations in these countries are ready for democracy. My short answer was, “No, they are not ready”. However, because this is a very timely and complex question, I have decided to give it here more than a terse, short answer.

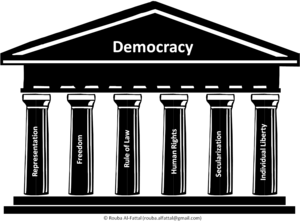

Democracy, by definition, is “the rule of the people” from the Greek words “demos” (people) and “kratos” (rule). The will of the people is manifested most visibly through the electoral process. Hence, there is no democracy without fair and free elections in which the people chose their representatives. Consequently, representatives in a democratic system obtain their legitimacy through the very act of election and use these elections as a barometer to monitor their popularity over time. But despite the fact that elections are a necessary pillar of democracy, they are not sufficient to consolidate a democratic system. Democracy is about much more than elections, and can only stand the test of time if other pillars are simultaneously present.

No democracy can survive without the protection of basic freedom of expression, belief, and press. In Egypt, for instance, since the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) “Justice and Freedom Party” ascended to power through elections, it took control of public media and has continued its crackdown of other media outlets – especially those that are seen as critical of the group or of President Mursi. However, with a lack of real political opposition, the media became the main opposition bloc for the MB. Over the past year, the Brotherhood and its allies have followed several tactics in terrorizing journalists and TV hosts, including violence, legal action, press statements, and speeches made by the President. The MB’s main argument is that liberal commentators on these channels blur the line between constructive and hostile criticism. This defensive reaction is a common cultural problem in Arab societies in general, which have grown – under years of dictatorship – unaccustomed to open criticism from domestic sources and consider any critique a personal insult that must be prevented and punished.

No democracy can survive without the protection of basic freedom of expression, belief, and press. In Egypt, for instance, since the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) “Justice and Freedom Party” ascended to power through elections, it took control of public media and has continued its crackdown of other media outlets – especially those that are seen as critical of the group or of President Mursi. However, with a lack of real political opposition, the media became the main opposition bloc for the MB. Over the past year, the Brotherhood and its allies have followed several tactics in terrorizing journalists and TV hosts, including violence, legal action, press statements, and speeches made by the President. The MB’s main argument is that liberal commentators on these channels blur the line between constructive and hostile criticism. This defensive reaction is a common cultural problem in Arab societies in general, which have grown – under years of dictatorship – unaccustomed to open criticism from domestic sources and consider any critique a personal insult that must be prevented and punished.

Another aspect that is considered a litmus test for any democracy is respect for the rule of law. To have an effective democracy there must be a separation between the legislative, the executive and the judicial branches of government. In democracies, everyone – from the head of government to the regular person – is equal before the law. The law in such cases is implemented by the police, which is considered an instrument to serve all tax-paying citizens impartially. By contract, if we look at Egypt in the last nine months we see the exact opposite. The President wants to preside over the judiciary, and his confrontations with the judiciary have nearly brought the country to the brink of chaos. Citizens do not respect the police, and the police on the other hand are not keen on restoring public order. This social norm in the Arab world, total disregard for the law and the police, is caused by an imbedded mistrust due to a past riddled with generations old grievances and rampant injustice. This mistrust is the result of a government which entered the stage democratically and with high expectations for the future but which slid slowly but surely into tyranny. Plato, in his classification of the five systems of governments, describes the lowest form of government as the tyrant whose lawless behavior leads to his own self-imprisonment and alienation, which we have started witnessing in Egypt.

Human rights are another major pillar for any democracy to sustain itself. That is because a democracy is not the tyranny of the majority. To the contrary, a modern democracy is measured by how much the majority in power is restrained by its respect for minority rights. There are different minority rights that should be protected including ethnic, religious, linguistic, racial, and gender rights. No society can call itself a democracy when, for instance, its women are disrespected or targeted. If we look at the new Egyptian Parliament, the women are scarce; actually, lower than they were before the “Arab Spring”. Reported cases of female harassment in Egypt have been on the rise since 2011, to the point that there are documented cases of group rape in which the accused have been left uncharged and unpunished. To the contrary, often MB spokespersons lay the blame on the victims instead of the perpetrators for being at the wrong place (meaning outside their homes). Even the Egyptian Information Minister, Salah Abdel-Maksoud, has been accused of sexual (verbal) harassment by three different female reporters; the accusations came following public comments he made which were laden with sexual overtones – all of that while his MB colleagues in power are making excuses for him and pledging their support.

In order to protect minority rights a political system must also be a secular one. Secularism, or the separation between religion and the state, is a basic tenet of and indivisible from democracy. Without secularism we end up creating an illiberal-democracy: one that favors the majority group, with their belief system, over other groups within society. Thus, the lack of secularism creates two-tier citizenship: those who belong to the majority and “the others”. The laws of the majority are then automatically applied to the minority without taking into account their specificities and basic rights. For instance, under the Islamist MB rule in Egypt, the religious and civic rights of the minority Copts – who are the native Christians of Egypt – are at great risk. Many feel they must leave their country due to their marginalization, neglect, and/or harassment by the new government. It is nothing less than tyranny when those in power try to impose their own laws, values, and customs on everyone else in society – while prosecuting anyone who refuses to conform to their views. In a real democracy, there are universal rights and laws that apply to all citizens, equally, despite their personal beliefs. Religion in a secular state is considered a private and not a public good. Secularism does not mean that a country cannot have a specific or dominant religion or religious symbols as a part of the state’s identity, which is actually the case in the United States. It merely means that the law is universal and all citizens are treated equal before it.

This discussion brings us to the most important pillar or democracy, namely individual liberty or the individual right to choose. Individualism is indeed a building stone to any democracy and a sacred right in Western cultures. However, individualism is lacking in Arab cultures, which constitutes the biggest hurdle in achieving a democratic system. In an individualistic society everyone has the right to “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness”; Governments are merely there to ensure these rights. Hence, there is a direct relationship between the individual and the law; the rights of the individual are above the rights and interests of the group. Arab societies, on the other hand, are still tribal and clannish in nature. These societies tend to put the rights of the group (be it Brotherhood, or collective/“ummah”) before the rights of the individual. In a country like Egypt, the closed MB group – with its own customs, values, and laws – wants to overpower the individuals they now rule, and to wipe away their old identity in order to create (overnight) a new identity that matches with the group’s identity. In a country like Egypt, the political party becomes a clan that sacrifices the rights of the individual for the collective good of the clan (despite the absence of a legal definition for an entity, since laws relate mainly to the individual and his relationship with the institutions or property and not to a group). Indeed the takeover of power by the MB in Egypt would not have been considered nearly as catastrophic if it were an actual political party (with a religious reference based on a consensual legal framework operating within an independent modern-state). But this group, or clan, lacks any universal legal definition or clear political framework, and its loyalties are more to the Islamic ummah/collective than to Egypt. It has tried to abolish individual freedom in a fascist way that imposes rules about how citizens should talk, dress, and act. Even the parties which the MB claims to model, such as the Christian Democrats in Europe, would never try to impose a uniform lifestyle or a behavior on people (not even their own party members), or replace laws that are accepted universally, or give instructions to people on how to lead their daily lives – things which the Church has abandoned centuries ago.

The sense of individual liberty, however, is not an acquired right. It is an organic right that grew within a defined framework which acquires its power and legitimacy through a set of laws that are agreed upon unanimously by society over a very long period. A society may need to pass through many failed, perhaps bloody and bitter experiences before it learns to survive, tolerate and coexist. This is why a burgeoning democracy needs experience, time, and open minds that are willing to learn from experience. Thus, the liberals in most societies make the perfect fertile ground for democracy to flourish. Unfortunately, as the recent elections in the Arab world revealed there are not enough liberal Arabs to beat the Islamists who outnumber them (even if by a slight margin).

The key questions then are, who are the liberal Arabs and where are they in all of this? The term liberal is indeed an umbrella term covering Muslims, Christians, Jews, Baha’is, Buddhists, atheists, etc. – as long as they are secular and believe in individual liberty and the rule of law. The liberals, however, remain the persecuted minority in the Arab world. This is why the development in Syria is very alarming. Although many liberal Arabs long for democracy, they realize that the uprising in Syria and elections after Assad will not bring freedom. It is a catch-22: you know that the same democratic elections that you dream of will only bring the Islamist tyrants you most dread. After observing the Palestinian and Egyptian experience with democracy, US President Barack Obama understands this dilemma, which makes him very reluctant to act in Syria. In closed circles you hear Arab liberals asking the million-dollar question, “Isn’t it better to have the tyranny of Assad than the tyranny of the Islamists”? Liberal Arabs wistfully realize that they are stuck between a rock and a hard place for many more years to come.

Democracy is not only about elections and ballot boxes, it is instead a process and what happens between elections is what really matters. Although this statement might seem redundant and intuitively clear to a Westerner, it is not so to an Islamist. The democratic structure needs several pillars to stand on; otherwise, the system will come crumbling down on the heads of the electorates. While many of the examples used here are from the Egyptian case they are not exclusive to it. The Arab world, as a whole, is not yet ready for democracy. Not because Arabs are not longing for democracy and freedom, but because the Islamist majority is still lacking the other pillars to have an effective and lasting democracy, mainly respect for individual liberty and universal laws that apply equally to everyone in society.

Comments

Please login to post comments.