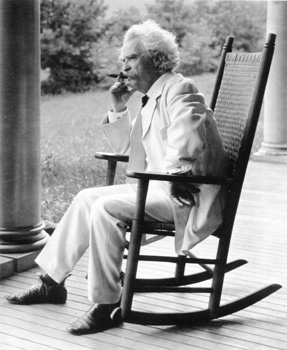

It is a pity that political correctness has driven Mark Twain out of style. A generation ago, Samuel Clemens (whose nom de plume was “Mark Twain”) was both an iconic author of children’s stories (Tom Sawyer, Prince and the Pauper) and regarded as one of the “greats” in American literature for the classic Huckleberry Finn. Although “Tom” and “Huck” were often presented as a duality of “boys’ stories,” Huck was anything but a child’s tale with its sophisticated story of adult duplicity and mendacity along with Huck’s efforts to get a slave friend, “Jim” to safety.

It was, however, Twain’s utilization of the unspeakable/unprintable “N word” to identify Jim that has driven the book almost into the brown-paper wrapper status previously reserved for steamy Henry Miller sex novels not published in North America until the 1960s. And with this opprobrium for Huckleberry Finn, undeserved as it is, has also come a general neglect of the rest of Twain’s body of work, notably his travel books such as Roughing It, Innocents Abroad, and Life and the Mississippi. This is not to say that Twain does not offend—at least not offend 21st century readers—with blunt sociological comment on aboriginal North Americans in Roughing It and contemptuous criticism of residents of the Middle East (“Holy Lands”) in Innocents Abroad. Still the acuity of his observations and the trenchant quality of his prose have a 21st century style, avoiding the over-inflated bombast of most of his 19th century contemporaries.

It was, however, Twain’s utilization of the unspeakable/unprintable “N word” to identify Jim that has driven the book almost into the brown-paper wrapper status previously reserved for steamy Henry Miller sex novels not published in North America until the 1960s. And with this opprobrium for Huckleberry Finn, undeserved as it is, has also come a general neglect of the rest of Twain’s body of work, notably his travel books such as Roughing It, Innocents Abroad, and Life and the Mississippi. This is not to say that Twain does not offend—at least not offend 21st century readers—with blunt sociological comment on aboriginal North Americans in Roughing It and contemptuous criticism of residents of the Middle East (“Holy Lands”) in Innocents Abroad. Still the acuity of his observations and the trenchant quality of his prose have a 21st century style, avoiding the over-inflated bombast of most of his 19th century contemporaries.

Life on the Mississippi is far from the greatest of Twain’s travel accounts. It is a somewhat jumbled pastiche of the history of steam boats immediately before the Civil War and nostalgia for a lost era in which Twain travels, as an older (and famous) man, the Mississippi that he learned as a river boat pilot a generation earlier. Fascinating albeit flawed, Life has doubtless inspired subsequent generations to take that “once-in-a-lifetime” steamboat Mississippi cruise to seek, even at many removes, Twain’s sense for the Mississippi River as the central artery of the United States.

It was under Twain’s impetus that in November 2008, we took a “bucket” trip combining a first-in-a-lifetime visit to New Orleans with a once-in-a-lifetime Mississippi River steamboat trip from New Orleans to Vicksburg and back.

New Orleans. For most Americans and Canadians, New Orleans used to epitomize the Marti Gras carnival, “Cajun” cuisine, and the mélange of racial and ethnic mixes that saw the city controlled by multiple European states before passing into U.S. hands with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Now, however, the first thought is often “Katrina” and the hurricane that revealed comprehensive failures in U.S. disaster planning and management the consequences for which continue to reverberate.

Our first surprise was the French Quarter—old New Orleans. Media had suggested that it had survived because it was on “high ground.” My mind’s eye pictured the Quarter built on a bluff substantially above the river akin to Natchez, Baton Rouge, or Vicksburg. Instead, the Quarter is only modestly above Mississippi River level—the problem was that other sections of the city were substantially below normal, let alone hurricane driven, water levels. But the Quarter is quite sufficient for the tourist—even without pre-Lent parades and hoopla. Whether you are dining at K-Paul’s featuring master chef Paul Prudhomme or munching a “poor boy” sandwich, you will be getting a memorable meal.

The Quarter is saturated with early North American architecture and replete with ante-bellum history that inter alia provides a more nuanced vision of slavery than available in Northern abolitionist literature. For those seeking a touch of the macabre, the above ground cemeteries and mausoleums—where every cemetery seems to mix disintegrating ruins with whited sepulchres—you can visit the tomb of a “Voodoo Queen” and wonder just what those leaving tokens and coins are seeking?

For the modernist, there is the still emerging World War II museum, which is headed toward becoming the best North American museum addressing this conflict and built around amphibious landing craft used at D-Day Normandy and countless Pacific Ocean island assaults. These “Higgins boats” evolved from swamp boats used in the bayous of Louisiana and were produced by the thousands in New Orleans during WWII.

Indeed, the city may never recover to its pre-Katrina geography and demography. Rebuilding in areas that exist only because of dikes and water control will require levels of insurance unlikely in current fiscal realities. And consequently we skipped visiting the “disaster tourism” sites, just as we have never visited “ground zero” in NYC as we are not voyeurs into the tragedies of others.

Steam-boating the Mississippi. There are a variety of cruise/steamboats making trips of different distances on the River. Once the epitome of luxury for 19th century America and the primary mechanism for moving passengers and cargo through the central artery of the United States, they are now tourist spectacles—historic in style, closely replicating their ancestors, and designed for traveling comfort. The more famous steamboats, the American Queen and Delta Queen, are now in temporary retirement (we took the last official voyage of the American Queen). It was amusing to—at social security age—be among the youngest of the passengers. Consequently, nightly nostalgia entertainment had more of a taste of the 1930s-40s than any more contemporary era. But we were a well-fed assembly: the aphorism was that “you come on board as passengers, but you disembark as cargo.”

American Queen had a standard set of port calls: Natchez, Vicksburg, and Baton Rouge as the primary points. Natchez featured a selection of ante-bellum mansions (the city was fortunate enough to be seized quickly by Union forces during the Civil War and thus the mansions were only looted by occupying troops rather than being burned to the ground in scorched earth fighting). They provided a quick reminder that the White House in Washington DC was hardly palatial when compared to the home of a successful Southern plantation owner.

Now a sleepy small town, Vicksburg was the primary fortified bastion of the Civil War South. It served as the connecting point between the east and west of the Confederacy as well as preventing the Union from fully exploiting control of the Mississippi River but fell after an extended siege. General Ulysses Grant’s military maneuvers designed to isolate Vicksburg and defeat its supporting forces remain text book illustrations of tactical brilliance (and prompted his promotion to command of the Union army in the east). The seizure of Vicksburg came virtually simultaneously with the Union victory at Gettysburg—and sealed Southern defeat.

Baton Rouge, as the capital of Louisiana, still heavily reflects the aura of Huey Long. Assassinated under still disputed circumstances in 1935, “the Kingfish” ran the state as a personal fiefdom featuring semi-dictatorial corruption. With clever populist demagoguery and radio commentator wit, Long would have been a serious rival for the presidency against FDR, not in 1936, but in 1940 when Roosevelt was facing the three-term shibboleth, the Depression remained unabated, and isolationism was popular. Baton Rouge also features a governor’s mansion built for Long as a duplicate of the White House (down to the positioning of the light switches, reportedly so he would not have to relearn their locations when he moved to Washington). Equally impressive is the state legislature, a 32 story replica of NYC’s Empire State building, built in 14 months—a construction time noteworthy for those 21st century builders for whom remodeling Ottawa’s Peace Tower took considerably longer. Doubtless there was corruption in construction, but the legislative building looks considerably better than most structures that are 70 years old.

But in passing, a traveler also learns that the aphorism, “all politics are local” is pointedly true outside the Washington Beltway. One week after our historic national presidential election, the Baton Rouge Advocate headlined “Woman Slain in Klan Rite” with no post-election coverage of the president-elect.

Nevertheless, the primary actor on the cruise remained the River—listed at 2,350 miles, the length regularly changes as the Mississippi has repeatedly changed course over the centuries both shortening itself by cutting through “S” shaped bends and lengthening with breaks through dikes into “old” river beds. With 257 tributaries, it drains 41 percent of the U.S. from 31 states, it remains the most efficient method for moving bulk cargo as one standard barge can carry 15 train car or 58 truck loads of material (and a 15 barge tow is normal). Although it is “out of sight; out of mind” for the majority of Americans distributed on the east and west coasts, it is the primary geographic characteristic of the United States; it has shaped our past and will continue to mold the future.

Comments

Please login to post comments.