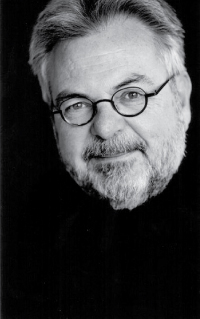

If there’s any doubt that Michel Tremblay is a national resource, all you have to do is look around . He’s everywhere. Tremblay’s latest play – his 30th– Fragments des mensonges inutiles, is at the Theatre Jean Duceppe until October 17. His fifth novel, La Traversée des sentiments, comes out in November, and a musical based on his classic, Les Belles-Soeurs, (lyrics by René Richard Cyr and music by Daniel Bélanger) will be staged next spring at Théâtre d'Aujourd'hui, and is already a box office hit. Tremblay is also doing the French translation of Steve Gallucio’s farce, Piazza San Domenico, which opens the Centaur season Oct. 6 , Michel Tremblay is also a character who banters with Jack Kerouac in George Rideout’s play, Michel & Ti-jean, at the Centaur in February. A production of Albertine in Five Times is at the Shaw Festival until mid October, and next year, Stratford will produce For The Pleasure of Seeing Her Again. A gentle, bespectacled bear of a man with a full moon face, Tremblay turned 67 in June. He helped create a cultural revolution in Quebec when he broke with convention and first spoke to audiences in working class slang with Les Belles-Soeurs. A film buff, with a taste for B-movies, Tremblay’s plays, peopled with melodramatic misfits, have often been compared to those of Tennessee Williams, but Tremblay’s characters are much more visceral than anything William created. Le Monde said it best; “He is an inventor of language who takes the sounds from the mouths, minds and flesh – living words still warm – then uses them to build coloured palaces of hard stone.” Embarrassed by the attention, Tremblay is nevertheless , clearly aware of his place as a master who blends nostalgia with hard core reality. Fragments des mensonges, like many of his other plays, is unique in that it allows characters from the past to relate and interact with those in the present. “I am pretentious enough to believe that I invented this kind of theatre,” says Tremblay. ’’I invented it. It belongs to me. I like to play with shifts in time and go from past to present. I always try to let it serve me in different ways.”

A gentle, bespectacled bear of a man with a full moon face, Tremblay turned 67 in June. He helped create a cultural revolution in Quebec when he broke with convention and first spoke to audiences in working class slang with Les Belles-Soeurs. A film buff, with a taste for B-movies, Tremblay’s plays, peopled with melodramatic misfits, have often been compared to those of Tennessee Williams, but Tremblay’s characters are much more visceral than anything William created. Le Monde said it best; “He is an inventor of language who takes the sounds from the mouths, minds and flesh – living words still warm – then uses them to build coloured palaces of hard stone.” Embarrassed by the attention, Tremblay is nevertheless , clearly aware of his place as a master who blends nostalgia with hard core reality. Fragments des mensonges, like many of his other plays, is unique in that it allows characters from the past to relate and interact with those in the present. “I am pretentious enough to believe that I invented this kind of theatre,” says Tremblay. ’’I invented it. It belongs to me. I like to play with shifts in time and go from past to present. I always try to let it serve me in different ways.”

Fragments des mensonges inutiiles is a psychological drama that explores attitudes toward homosexuality and whether anything has really changed over the past 40 years. Like many of Tremblay’s plays, the approach is clear eyed and clinical. The characters on the left hand side of the stage inhabit the grand noiceur of the 50s; those on the right hand side, live in the politically correct beige world of the present. Jean Marc (Olivier Morin) and Manu (sGabriel Lessard) command the stage as lovers across the divide, connected only by their sexuality. All dramas are about lies, and this play is no exception. The lies in this play are the lies we tell each other and ourselves about homosexuality. In spite of huge strides that have seen equal rights for gays in the workplace, gay marriage and a more tolerant attitude toward homosexuality, many adolescents are terrified at the thought of coming out to family and friends. ”We have evolved as a society, certainly,” says Tremblay, “To be a homosexual in Quebec is no longer taboo. But just because society has evolved, doesn’t make it any easier for the individual, for those who would like to be completely at ease with their sexuality and open about it to others.” Forty years ago, for example, it would not have been possible to stage the opening scene which depicts the nude, teenaged lovers in a graphic sexual embrace. Like shadows in a dream, the other characters flit through the piece. A priest of the 50’s, (Roger La Rue) a psychiatrist from 2009 (Gabriel Sabourin), Jean Marc’s parents, (Maude Guerin and Normand D’Amour) and Manu’s politically correct mother and father, (Linda Sorgini and Antoine Durand). Like many of Tremblay’s plays, the approach is clear-eyed and clinical without much sensuality. Director Serge Denoncourt shows his affinity for Tremblay’s work, eliciting electric performances from his cast, especially Maude Guerin as Jean Marc’s mother, Nana. Lessard and Morin are mirror images of each other, and totally unselfconscious in their demanding roles. The play is as much a piece of verbal music as it is a drama. Like a concerto, there are movements, solos, spoken duets and quartets.

“When critics say my work is realistic, that’s an insult,” says Tremblay, “The public must always be aware that they are theatrical. Theatre exists to be aggressive. It has to be aggressive to be interesting. Starting with Belles Soeurs audiences must surely know the actors are there inhabiting a role, and trying to convince people to believe that what they are seeing is real, even though they know very well that’s not the case.

Comments

Please login to post comments.