“I never give any information about me in writing because you can tell at a glance my paintings contain the most accurate information about me. I have no intention of revealing to the astonished bourgeois and contemporaries the depths and abyss within my soul,” the German artist Otto Dix once wrote to a friend. That may explain why the engrossing exhibition running until January at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Rouge Cabaret, A terrifying and Beautiful World, is both an immersive experience and a revelation. Not only do the 220 works on display examine the career of Otto Dix but follow a chronology that emphasizes the peculiar mix of decadence and despair which not only represents “the abyss within” his soul, but the dehumanizing times through which he lived.

“I never give any information about me in writing because you can tell at a glance my paintings contain the most accurate information about me. I have no intention of revealing to the astonished bourgeois and contemporaries the depths and abyss within my soul,” the German artist Otto Dix once wrote to a friend. That may explain why the engrossing exhibition running until January at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Rouge Cabaret, A terrifying and Beautiful World, is both an immersive experience and a revelation. Not only do the 220 works on display examine the career of Otto Dix but follow a chronology that emphasizes the peculiar mix of decadence and despair which not only represents “the abyss within” his soul, but the dehumanizing times through which he lived.

Born in 1891 Dix served with the German Army during the First World War, emerged from the trenches as something of an enfant terrible and earned a reputation for his excess and outrage as an artist during the Weimar Republic of the 1920s and 30s. The Third Reich, however, considered his art “degenerate” and confiscated many of his pictures. Co-opted by the Nazis, Dix sacrificed his art to save his hide and served in the German Militia during the Second World War. He was taken prisoner by the French, and after the War lived in relative seclusion painting inoffensive, toxic landscapes until his death in 1969. If art can be said to be the barometer of a civilization, this represent some of best art of the period between the two world wars, indelible in the imagination.

Born in 1891 Dix served with the German Army during the First World War, emerged from the trenches as something of an enfant terrible and earned a reputation for his excess and outrage as an artist during the Weimar Republic of the 1920s and 30s. The Third Reich, however, considered his art “degenerate” and confiscated many of his pictures. Co-opted by the Nazis, Dix sacrificed his art to save his hide and served in the German Militia during the Second World War. He was taken prisoner by the French, and after the War lived in relative seclusion painting inoffensive, toxic landscapes until his death in 1969. If art can be said to be the barometer of a civilization, this represent some of best art of the period between the two world wars, indelible in the imagination.

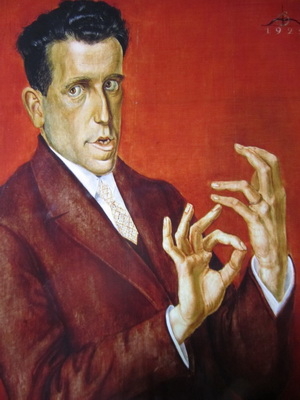

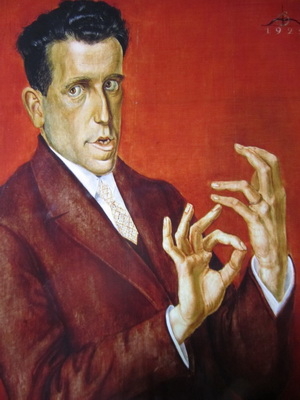

The MMFA exhibition is divided into six themes: The Trenches, Streetscapes, The Brothel, The Portrait Gallery, Art and Nazism and The Landscapes. Self portraits carry a truth of how an artist wants to be seen; one painted in 1912, shows a youthful, if rather severe-looking Dix holding a carnation; the second, painted just two years later reveals that the self is not a stable thing, it depicts him with a shaved head, a deeply disoriented soldier deformed by war.

His grotesque portrait of the dancer, Anita Berber, is a masterwork, which instantly reveals the loss of meaning, values and morality after World War I. His shocking Little Girl in Front of a Curtain a painting of a nude 12-year-old wearing nothing but a pink bow in her hair, invites debate over whether the work is exploitive, pornographic, or legitimate artistic expression that represents society’s ultimate moral breakdown. The show, however, is built around his outstanding Portrait of The Lawyer Hugo Simons one of his first paintings executed in oil and tempera which the MMFA acquired in 1993 from the Simons family in Montreal when it was in danger being lost to another country.

His grotesque portrait of the dancer, Anita Berber, is a masterwork, which instantly reveals the loss of meaning, values and morality after World War I. His shocking Little Girl in Front of a Curtain a painting of a nude 12-year-old wearing nothing but a pink bow in her hair, invites debate over whether the work is exploitive, pornographic, or legitimate artistic expression that represents society’s ultimate moral breakdown. The show, however, is built around his outstanding Portrait of The Lawyer Hugo Simons one of his first paintings executed in oil and tempera which the MMFA acquired in 1993 from the Simons family in Montreal when it was in danger being lost to another country.

The exhibition, as the MMFA’s director and chief curator Nathalie Bondil explains, offers rare insight into a tumultuous period of history. “It’s a snapshot of the first half of the 20th century, its upheavals, its ruptures, its total disintegration. At the same time it’s a cautionary tale, the story of immigration, of renewal, of re-inventing yourself a colossal symbolic door to understanding.” In his forward to the handsome exhibition catalogue, Olaf Peters, curator of New York’s Neue Galerie, who initiated the show, says the works mirror the myth of the so called roaring 20s, and reflect the “political and social ruptures and fault lines of their day.” Not to be missed, the show is at the MMFA until the New Year.

Comments

Please login to post comments.