Two important international meetings took place in November – the G20 met in Seoul and NATO met in Lisbon. While one is an international economic forum and the other is a military alliance originally conceived to prevent Soviet agression, their outcomes are linked by a lack of vigour and funding. The flaccid direction from both of these summits does not bode well for the near future of economic cooperation nor for a coordinated response to serious threats from Iran, the Taliban/Al Qaida and North Korea.

First to the G20 in Lisbon – where the member states complained about each other’s policies and resolved to “monitor” each other’s bad behaviour for possible correction in the future. In response to China’s refusal to allow its currency to rise in value enough to reduce serious trade imbalances and the US’ refusal to reneg on debasing the world’s reserve currency, the G20 have created the “Mutual Assessment Process (MAP) to promote external sustainability. (We) will strengthen multilateral cooperation to promote external sustainability and pursue the full range of policies conducive to reducing excessive imbalances and maintaining current account imbalances at sustainable levels.”

The gobbledegook above basically says that the G20 intend to watch member states pursue their race to the bottom in currency valuations and if it gets too bad, call each other on the carpet. Since China and the US will not change their respective policies, one can expect that the US Dollar will continue to lose value as a reserve currency and currency diversification among creditor nations (like China and the oil producers) is likely to push up other currencies as a result, whether those nations desire it or not.

Russia, for example, has announced that it has added the Canadian Dollar to its reserves. Other nations will certainly take note. As well, gold purchases continue among the central banks of creditor nations since it is seen as a true hedge against further USD devaluation with the second round of quantitative easing (QE2) now underway in the US. When he US Federal Reserve announces that it intends to purchase $600 billion in US government debt to inject cash into the economy, learned economists around the world translate this policy into its more familiar moniker, “printing money.” The Chinese would be more vocal in their disappointment with this policy except that they already hold about $800 billion in US government debt among their $2 trillion or more in reserves. The more noise they make, the less their investment will be worth. To those who believe that the bull market in bonds will continue indefinitely, a careful review of G20 policies would indicate that debtor nations will engage in debasement and the ensuing inflation to reduce their debt to GDP ratios in the long run.

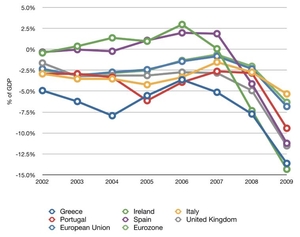

Among European nations, the revolving credit crisis continues. Greece gave way to Ireland; Portugal is next, and then Spain. Bond traders are making the rounds of the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) and pushing bond prices down (and yields on debt up) as they expose the overextension of each sovereign nation’s debt. Even though the IMF has just announced a doubling of its capitalization to $750 billion USD, this would not be enough if the IMF alone had to bail out all the PIIGS. Germany cannot be called upon to save all other nations, even with the aid of the IMF. Spain, whose debt crisis is scheduled for early in 2011, is too big to save and too big to fail. So far with Greece and Ireland, the debt reorganization packages have not forced any debt holders to “take a haircut”, meaning, write off part of their debt. With Spain, that will have to change, since there is not enough money in IMF and German pockets to “extend and pretend” (a real estate term currently popular in the US, when debt is rolled over to be dealt with hopefully under better times later on)

Among European nations, the revolving credit crisis continues. Greece gave way to Ireland; Portugal is next, and then Spain. Bond traders are making the rounds of the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) and pushing bond prices down (and yields on debt up) as they expose the overextension of each sovereign nation’s debt. Even though the IMF has just announced a doubling of its capitalization to $750 billion USD, this would not be enough if the IMF alone had to bail out all the PIIGS. Germany cannot be called upon to save all other nations, even with the aid of the IMF. Spain, whose debt crisis is scheduled for early in 2011, is too big to save and too big to fail. So far with Greece and Ireland, the debt reorganization packages have not forced any debt holders to “take a haircut”, meaning, write off part of their debt. With Spain, that will have to change, since there is not enough money in IMF and German pockets to “extend and pretend” (a real estate term currently popular in the US, when debt is rolled over to be dealt with hopefully under better times later on)

The chart above shows the PIIGS annual budget deficits up to 2009, with the UK and Eurozone nations thrown in for comparison purposes. It demonstrates that all of the major European powers will have to make serious budget cuts over an extended period of time, and no area of spending will be considered taboo. That will include military spending, and that’s where the NATO summit comes into this equation.

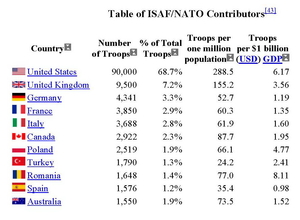

The top contributors of troops to the international effort in Afghanistan are NATO members, and most of them are Europeans. The chart here details the current levels of commitment in the field as of late 2010.

Keeping a solider deployed in a combat environment costs about $1 million USD per year; it’s no wonder that the Eurozone nations want to extract themselves from Afghanistan as quickly as possible. After nine years of war, the Taliban is still able to mount credible resistance and seeks refuge in Pakistan to regroup over the winter months; NATO does not dare intervene overtly in the Pashtun region of Pakistan due to fears of further destabilizing that nation. With no end in sight, NATO has picked a date to remove itself from the battlefield: 2014. One should not expect all the major contributing nations above to remain fully committed in their current roles until then – Canada will revert to a training role early in 2011 which will cut its troop commitments and costs by more than half. The European nations in the midst of budget crises and dissipating voter confidence look longingly at Canada’s extraction from a combat deployment role and wonder how they can revise their own commitments downwards, no matter how small they may already be.

Keeping a solider deployed in a combat environment costs about $1 million USD per year; it’s no wonder that the Eurozone nations want to extract themselves from Afghanistan as quickly as possible. After nine years of war, the Taliban is still able to mount credible resistance and seeks refuge in Pakistan to regroup over the winter months; NATO does not dare intervene overtly in the Pashtun region of Pakistan due to fears of further destabilizing that nation. With no end in sight, NATO has picked a date to remove itself from the battlefield: 2014. One should not expect all the major contributing nations above to remain fully committed in their current roles until then – Canada will revert to a training role early in 2011 which will cut its troop commitments and costs by more than half. The European nations in the midst of budget crises and dissipating voter confidence look longingly at Canada’s extraction from a combat deployment role and wonder how they can revise their own commitments downwards, no matter how small they may already be.

In the old days of the Vietnamese war, this was called “Vietnamization” – getting the host nation’s troops to do their own fighting. It didn’t work in Vietnam, and at the moment there is no reason to imagine that the Afghan army would be able to sustain the fragile, marginal and corrupt Karzai regime. It is for this reason that US commanders are beginning to look at their opponents as “good” Taliban, those that can be co-opted, and “bad” Taliban, those firmly entrenched with Al-Qaida. It worked in Iraq with some of the Sunni militants, and it will have to work in Afghanistan if the NATO plan for gradual extraction will have a chance of succeeding.

It is never good strategy to tell your enemy when you plan to remove your best troops from the battlefield. The Taliban are likely to engage in backroom negotiations with the ISAF/NATO forces to curtail significant military offenses while they prepare for the day that they will face purely Afghan troops on the ground. The Afghan nation has never been held by an invading army for any significant length of time for nearly 1000 years and waiting out another set of invaders for four years is no big deal – especially if you know that they are out of money.

The G20 and NATO are each practicing their own game of “extend and pretend”, keeping things going in the hope that conditions will be better at a later date and the problem will be easier to deal with. Well, the impending Spanish debt crisis, the Iranian nuclear threat and an offensive North Korea are unlikely to create sunnier days for either organization. It’s a bit like running from a crumbling building to one about to catch fire – the self-congratulatory phase is likely to be fleeting and will give way to grave disappointment with the outcome.

Comments

Please login to post comments.