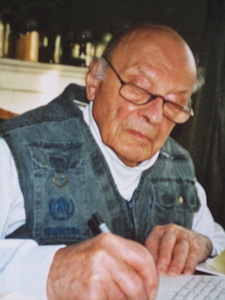

Maynard Gertler was an innovative farmer, civil libertarian, and the headstrong Montreal publisher who was the first to market books by French-Canadian authors in English Canada during the Quiet Revolution so the rest of the country could appreciate what was happening in Quebec in the 60s and 70s.

Gertler was the founding editor of Harvest House Ltd , once described as “a one man university press,” Harvest House was the first to translate the works of Quebec writers such as Jacques Ferron, Victor-Levy Beaulieu, Anne Hébert, Yves Thériault and the poet Emile Nelligan.

Gertler, who was 94 when he died in Montreal on April 19, had several careers during his life-time. During the Second World War he worked as an economist for the U.S government , taught U.S, history at Cambridge, , and farmed most of his life. He was active in the Canadian Human Rights Foundation and was a former president of the Canadian Chapter of Amnesty International ..

“He was very bookish. Books were his vocation and his recreation,” said his son, Michael. “He was a free thinker and a resister. He was active in the fight against capital punishment and campaigned for nuclear disarmament. He also knew how to farm. He was a keen observer of farming in England, and with his wife’s support, had farms in Pennsylvania, Virginia and Ontario.”

Maynard Gertler was born in Montreal Dec. 1, 1916 . His parents , Hyman Gertler and Gertrude (Slover). had come to Canada before the First World War from what was then Austro-Hungary, with the Slovers settling in Ottawa and the Gertlers working on farms in an Irish settlement outside Montreal. Maynard and his older sister and younger brother were raised in Montreal where his father had a furniture factory. Maynard was a voracious reader, and by the age of 17 claims to have read all of the English, French and Russian classics. Unable to get into McGill University because of its restrictions against Jews, Gertler studied mental and moral philosophy at Queen’s University. There he became a self-described campus radical, active in the socialist League for Social Reconstruction and wrote reviews for the Kingston Whig Standard. After receiving his BA from Queen’s in 1939 he went to graduate school at Columbia University and became a U.S. citizen. When the Second World War began he was invited by one of his professors to join the Board of Economic Welfare and during the Roosevelt and Truman administrations worked for the U.S. government’s Foreign Economic Administration helping to pave the way for the industrial reoccupation of Italy and Japan.

Maynard Gertler was born in Montreal Dec. 1, 1916 . His parents , Hyman Gertler and Gertrude (Slover). had come to Canada before the First World War from what was then Austro-Hungary, with the Slovers settling in Ottawa and the Gertlers working on farms in an Irish settlement outside Montreal. Maynard and his older sister and younger brother were raised in Montreal where his father had a furniture factory. Maynard was a voracious reader, and by the age of 17 claims to have read all of the English, French and Russian classics. Unable to get into McGill University because of its restrictions against Jews, Gertler studied mental and moral philosophy at Queen’s University. There he became a self-described campus radical, active in the socialist League for Social Reconstruction and wrote reviews for the Kingston Whig Standard. After receiving his BA from Queen’s in 1939 he went to graduate school at Columbia University and became a U.S. citizen. When the Second World War began he was invited by one of his professors to join the Board of Economic Welfare and during the Roosevelt and Truman administrations worked for the U.S. government’s Foreign Economic Administration helping to pave the way for the industrial reoccupation of Italy and Japan.

He was drafted into the U.S. Army after Pearl Harbour, an experience he described , “as being chained to a rock.” because the military does not encourage “your right to think and act for yourself.” After the war he he worked in New York as a research director for John Grierson’s documentary film-production company.

Threatened by the rise of McCarthyism and the general intolerance in the U.S. toward left-leaning ideas, Gertler moved to England in 1953 to teach history at Cambridge. While abroad, he learned to grow pedigreed seed, and made a specialty of timothy, trefoil and alfalfa.

He returned to Canada in 1959 and started his publishing house with his first books, Pierre Laporte's biography of Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis, The True Face of Duplessis and the first translation of Jean-Paul Desbiens' The Impertenence of Frere Untel, a book that savaged Quebec’s system of education. Harvest House, he often boasted, was also the first publishing company to question the negative impact of Quebec nationalism. “We were never in doubt where foreshortened history, ethnic and language politics were leading,” he wrote in a family memoir.

In the late 1960s he teamed up with McClelland and Stewart in Toronto to publish educational material, but the partnership ended after two years.

“I never knew Maynard not to be passionate. He really believed in the quality of his imprint,” said Philip Cercone, executive director of McGill Queen’s University Press. ‘When he started Harvest House he was probably publishing as many scholarly books as any university press back then.., I admired him. But when he couldn’t get government funding for his projects, he could be combative. It was tough to introduce readers to an audience that didn’t know or care about French-Canadian writers. He believed you had to get the two solitudes talking to each other through their literature. He had an impressive list of titles.”

The books he produced reflected Gertler’s own passion for history, economics, literature, social justice and the environment. “The manuscripts we did not publish may well be as exciting as the ones we actually produced,” he wrote to a friend in 1996. “Good publishing is an intellectual, aesthetic, technical and judgemental task. It is very hard work. A fair return for effort and preparation – let alone a windfall – is almost unknown. .Books are not shoes or pants or motorcars, they are works of character. To weigh a publishing house by its numbers is irrelevant. The question is not how many titles did you publish, or how much money you made, but did you publish a good book.? But I would rather manufacture and sell a good pair of boots than publish and inferior book.”

Gertler sold Harvest House Ltd. to the University of Ottawa Press in 1995.

“He was a curmudgeon,” said Simon Dardick, co- founder of Montreal’s Vehicle Press. “He lived many lives, and he was very opinionated. He was also an inspiration. He influenced me and other publishers, such as May Cutler at Tundra Books to translate timeless Quebec literature into English even though he didn’t make very much money from it.”

Nine years ago Gertler was given both the order of Canada and Queens University’s Alumni Achievement Award. Receiving the double honours he said, was like “two asteroids hitting you at the same time.”

He leaves his wife of 68 years, Ann Straus a member of the prominent Straus and Stieglitz families of New York, and four sons, Michael, Alfred, Franklin, and Edward, nine grandchildren and a great-grandson. Their second son, Jeffrey died in 2005.

A memorial service is being planned.

Comments

Please login to post comments.