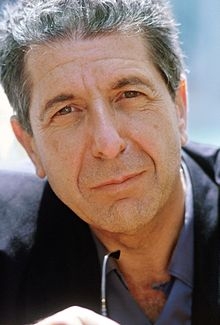

"You don’t know me from the wind/you never will, you never did,” Leonard Cohen wrote on the title track of his album, The Future, But that hasn’t stopped people who love his words and his mordant sense of humour from mourning the, poet, author and prince of mordant melancholy who died Monday Nov. 7 at the age of 82, three weeks after the release of his final album, You Want it Darker. His death was not made public until after the U.S. election was over.

Variously praised as “ the finest songwriter in America;” “the Lord Byron of rock'n'roll” , and as a mystic: "one of a tiny visionary company, the handful of rock or blues or folk singers who attempt to sort out the sense of the world with which they started."

Leonard Norman Cohen was born in Westmount, Sept. 21, 1934. His father, Nathan, was a wealthy clothing manufacturer, the first Jewish commissioned officer in the Canadian army who served with Canadian Expeditionary Force in World War I. He died when Leonard was 9. His mother, Masha Klinitsky, was a Russian rabbi's daughter who immigrated to Canada in the 1920s. Cohen learned to play guitar at a summer camp in 1950, "as a courting procedure," and the next year joined a high-school band, the Buckskin Boys.

He went to McGill where he was taught by Hugh MacLennan and Louis Dudek, discovered the works of Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, and where he forged a lifelong friendship with poet Irving Layton, who influenced his writing.

Cohen's first literary effort, a book of poetry called Let Us Compare Mythologies, won the McGill Literary Award. His first novel, The Favourite Game, was published in 1963. When Beautiful Losers, his book about the saintly Kateri Tekakwitha came out in 1967, it was acclaimed as one of the most daring experimental novels in Canadian letters. In 1969, he won the Governor-General's Award for another book of his poems, but he declined the honor. "I have a deep revulsion of being called a poet. Anything but that," he said at the time. "I'm a writer. I do feel that I am a rock'n'roll musician or a kind of Montreal Jewish blues singer." As Cohen told it, his decisive career move came in 1967 when he decided to go to Nashville and become a singer. "I did it to bail myself out of financial difficulties. I borrowed money to go. I had some songs and thought I had the country-and- western voice, so I decided to go to Nashville. "But on my way I got ambushed in New York by the folk-song renaissance."

Cohen's first literary effort, a book of poetry called Let Us Compare Mythologies, won the McGill Literary Award. His first novel, The Favourite Game, was published in 1963. When Beautiful Losers, his book about the saintly Kateri Tekakwitha came out in 1967, it was acclaimed as one of the most daring experimental novels in Canadian letters. In 1969, he won the Governor-General's Award for another book of his poems, but he declined the honor. "I have a deep revulsion of being called a poet. Anything but that," he said at the time. "I'm a writer. I do feel that I am a rock'n'roll musician or a kind of Montreal Jewish blues singer." As Cohen told it, his decisive career move came in 1967 when he decided to go to Nashville and become a singer. "I did it to bail myself out of financial difficulties. I borrowed money to go. I had some songs and thought I had the country-and- western voice, so I decided to go to Nashville. "But on my way I got ambushed in New York by the folk-song renaissance."

What he meant is that Judy Collins recorded what perhaps became his best known work, Suzanne. After that Cohen produced an album every three years or so, singing with a voice that one critic described as being "alternately diabolical and wise. And funny."

Cohen has won the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award, and Junos as best male vocalist and as songwriter of the year. In turn he created his own decoration, which he bestowed on fans: the Order of the Unified Heart. The lapel pin features the Star of David fashioned out of two hearts. He wryly reminded those who received it, that his award is "beyond all meaning and significance."

Cohen has a wide range of musical vocabularies – rock, country, blues and jazz. The Yiddish folk influence is also apparent in some of his songs like Take This Waltz, Everybody Knows or Closing Time.

"My mother sang beautiful Russian and Yiddish songs," Cohen once reminisced: "I love the violin, and I did put in those kind of Eastern European flourishes in a country- western song, which I think worked rather well. On Closing Time, that is.

“It wasn't that that didn't get it played in country-western territory, though. What the country singers and country radio programmers didn't like was that line 'The whole damn place goes crazy twice, once for the Devil and once for Christ,' which they found theologically offensive, although I could reconcile it with orthodox Christian thought.”

He is as familiar with Christian beliefs as he is with other religions. He once told a radio interviewer in Calgary that he admired Christ on a personal level. "Of all the people who have left their mark on history, I don't think there is a figure of Christ's moral stature," he said. "You cannot fathom his position, his inhuman generosity, which, if it was embraced, would overthrow the world." Cohen consolidated his religious philosphy in The Book of Mercy, a collection of his contemporary psalms published in 1984.

His musical career went into a slump the following year when he recorded Various Positions. It sold moderately well in Britain, but Columbia Records refused to release it in the United States. Oliver Stone raised Cohen's profile in the U.S. by using three of his songs for the soundtrack of Natural Born Killers: Waiting for the Miracle, Anthem and The Future.

Stone and Cohen, it seems, share the same apocalyptic view of the world.

In The Future Cohen wrote, "I have seen the future, baby, it is murder. I would say one of the consequences is going to be tremendous disorder, and the reanimation of the bloodlust which human beings seem to fall back on whenever they get mildly bewildered about their predicament," he explained.

In 2008, he discovered that his trusted business manager and former lover Kelly Lynch had stolen $5-million from him leaving him in financial distress. In order to replenish his bank account he mounted several exhausting world tours..

Asked once whether his apparent sense of despair was part of an act or genuine, he replied: "The emergency never ends. At times a peaceful self is born, but it never lasts, it never lasts. Everybody's heart gets broken. Everyone gets creamed. I don't think anyone beats the rap. What was the second last thing Christ said? Why hast thou forsaken me?"

Commentaires

Veuillez vous connecter pour poster des commentaires.