After the conclusion of what is probably the most important G20 meeting ever held, one can be forgiven for feeling optimistic. While unemployment in the US is at a quarter-century high at 8.3% and first world economies continue to contract, G20 leaders looked past their local economic miseries, resulting in an remarkable level of international commitment expressed in London. This solidarity was truly exceptional given the divergent opinions held by many going into the meeting. The US and UK wanted the continental Europeans to spend massively to stimulate their economies further, which was sternly rejected by France and Germany. The Europeans wanted an international financial regulator, seen as an unacceptable level of intervention by the US, and China bristled at EU efforts to cover Hong Kong and Macau in the quest to halt international tax havens, on which a compromise was brokered by President Obama at the last minute. If there was every a moment which could be defined as the pivot point towards recovery, this was probably it.

This does not mean that recovery is imminent, nor that it will be powerful enough to sweep away the mistakes that led to the longest recession since the depression of the 1930s. Recovery may begin in earnest towards the middle of 2010 rather than the second half of 2009; while a rising economic tide will lift all boats of state, some will rise higher in the water than others. Looking ahead, here is what the post 2010 world will probably look like in macroeconomic terms.

Massive debt and slow growth for the US and EU

The developed world’s governments were already carrying a high level of debt going into this mother-of-all-recessions; they will emerge far more severely indebted and will face painful political and economic decisions if they ever intend to bring their debt ratios back down. A study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) speculated that by 2012, the national debt to GDP ratio could hit 97% in the US, 80% in France, 79% in Germany, and 75% in the UK. Canada looks positively sparkling since our ratio will stay below 50% even if the Harper government’s predictions of a short 2-3 year period of deficits proves delusional; compare that to the IMF’s estimate for Japan, which could hit 224%. These debt levels are only exceeded by the post-WWII period and in many cases are not comparable to current conditions, since Europe and Japan’s economies had been wrecked by the conflict, while the US’ had been resurrected from the Depression by the massive industrialization required for the war effort.

Eventually, all of these nations will be forced to reduce government spending, increase taxes substantially, or do both. With aging populations, the baby-boomers of Europe and the US are unlikely to vote for politicians who cut spending, especially on health care which will be growing massively to match the demographics. The result will be heavy taxation on generations X and Y just as they approach their most innovative and productive years. This tax burden will reduce their desire to take risks, create companies, build wealth and innovate to create new business models to remain competitive against the economies of the developing world.

The result will be slower growth for decades and a lower standard of living for the middle classes who will be forced to repay the debts of their elders. In the past, innovators from the developing world emigrated to the US and Europe to put their ideas in motion; now they will most likely stay home or seek out other countries with more accommodating tax regimes and business environments in which to build their fortunes.

Enter China the Ascendant

China has the money, the talent, the military and the diplomatic moxie to displace the US as the superpower of the 21st century, and its political leadership knows it. Several salvos were fired earlier this year; warnings to the US to control its debt, with no assurances that China would continue to buy up US Treasury notes; a call to replace the US dollar with another currency as the international trading standard; and now, refusal to “recognize” efforts by the EU and US to curb international tax havens, but they did accept to “note” that these efforts were underway. For some, this last move was puzzling – why would China hold out on this point when it would seem to be in their best interests as well?

One can only imagine how China could use Hong Kong and Macau to attract all the international money that is being driven out of the EU and the US. These areas are SARs (Special Administrative Regions) whose regulations can be tailored to attract financial talent and capital without affecting the regulation of the mainland. As the US and the EU seek to tighten regulations over financial institutions, one cannot imagine that the financial instruments these nations are seeking to curtail are going to shrivel up and die; once you let a financial construct into the marketplace, you cannot make it go away. Financial creations like credit-default swaps, the undoing of insurer AIG, made billions of dollars (for a while) for its creators. Those who developed and managed these swaps and other similar products will be attracted to more liberal financial regimes in Hong Kong and Macau, and China will reap billions of dollars from providing them with a home. Think of the tens of billions in tax revenue that New York City received from the financial industry – if these jobs and instruments go to China, then New York, and London, Paris, Zurich and other financial capitals will never see those revenues again. China will be richer, and first-world re-regulation will be to blame.

One can only imagine how China could use Hong Kong and Macau to attract all the international money that is being driven out of the EU and the US. These areas are SARs (Special Administrative Regions) whose regulations can be tailored to attract financial talent and capital without affecting the regulation of the mainland. As the US and the EU seek to tighten regulations over financial institutions, one cannot imagine that the financial instruments these nations are seeking to curtail are going to shrivel up and die; once you let a financial construct into the marketplace, you cannot make it go away. Financial creations like credit-default swaps, the undoing of insurer AIG, made billions of dollars (for a while) for its creators. Those who developed and managed these swaps and other similar products will be attracted to more liberal financial regimes in Hong Kong and Macau, and China will reap billions of dollars from providing them with a home. Think of the tens of billions in tax revenue that New York City received from the financial industry – if these jobs and instruments go to China, then New York, and London, Paris, Zurich and other financial capitals will never see those revenues again. China will be richer, and first-world re-regulation will be to blame.

A plethora of failed states on the heels of Afghanistan and Iraq

If there is one lesson to be learned from the US-led interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, it is that it is cheaper, both politically and militarily, to equip a sovereign state to fix its own problems than to intervene and take over the keys to the kingdom. There is significant concern among the G20 that tens of states could crumble into civil war or outright dissolution if they are not offered financial salvation. According to the US think tank Fund for Peace, the list includes names like Somalia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Chad, Iraq, and Afghanistan (these are not surprises) but also includes potential failures like Pakistan, Lebanon, Egypt, Turkey (further down the list) and we should also add Mexico, given the massive drug violence that the federal government is unable to control. The list is longer than one would imagine, and it is disturbing. That is why the G20 committed another $500 billion USD in funding to the IMF to assist countries facing financial difficulty and an inability to raise debt in public markets.

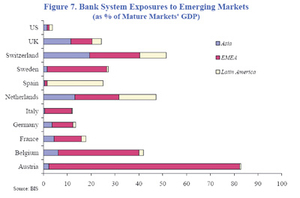

There is also a great deal of self-interest from the first world to prevent their existing financial commitments to these nations from evaporating. Many countries have significant banking exposure to the developing world that would prove catastrophic for their domestic economies in the case of default by a failed state. Consider the graphic illustrating the banking exposure of various mature economies to those of the developing world – if you were an Austrian banker, how well would you sleep at night without the IMF helping out your client states?

Even with the promised intervention of the IMF, there will be more failed states, some requiring massive financial intervention, and some perhaps military occupation. There will be more cases like Iraq and Afghanistan, though not for the same reasons – and these failed states will provoke international catharses well beyond the end of the recession.

Inflation will return to torture us all

In the past several days, Ben Bernanke of the US Federal Reserve Bank reaffirmed the Fed’s commitment to price stability and remarked that it could withdraw its financial stimulus in order to control an outbreak of inflation. Our own finance minister, Jim Flaherty, indicated in comments that inflation is going to be our long run concern as the recovery takes hold. All the debt being issued will have a hard time being repaid by its issuers, unless its value is undermined by an increase in inflation across all nations that allows the debt to be repaid in somewhat devalued dollars. We have become accustomed to inflation rates of 3% and below – this will not last. We will all live with a decade or more of 5-6% inflation, with the collusion of the US and EU central banks, in order to make repayable the massive debt issued by first world nations to exit the crisis. As a result, we will all be poorer, with our savings devalued by this policy. We can only hope that the stimulus packages will be successful, so that we will have the opportunity to earn back our lost savings though renewed economic growth. At the moment, this outcome is still uncertain – we will have to wait to see if the era of cooperation heralded at the end of the G20 meeting delivers on its promise.

Commentaires

Veuillez vous connecter pour poster des commentaires.