“The War of the Worlds, not the one from outer space happened right here,” Lillabit Bradley reminds us in David Fennario’s Motherhouse, a 90-minute monologue staged at the Centaur Theatre until March 23 to commemorate the centennial of the Great War.

Motherhouse is not so much a play as an arresting diatribe in search of one. As the protagonist, Bradley, who worked at the British Munitions Factory in Verdun when her brother went off to fight the war, Holly Gauthier-Frankel has her work cut out for her. She is an enjoyably talented, energetic actor who does her best to get the audience involved. She leads sing-songs, unleashes her wry, self-controlled anger and keeps us engaged even when the script turns into an awkward and sometimes incoherent polemic. It’s a strenuous part and Gauthier-Frankel occasionally seems flummoxed by the demands of playing a century old-character. In fact a 1916 photograph of female factory workers on their lunch break inspired Fennario to write the play. Motherhouse touches on the linguistic and religious issues, conscription, and labor strife which divided the country during the war. Anyone who took Fennario’s walking tours through Old Montreal knows that the playwright, now confined to a wheel chair with Guillain-Baree syndrome, isn’t one to let the facts get in the way of his searing, anti-capitalist, left-wing rants. And Motherhouse is no exception. For example, he occasionally confuses the Black Watch with the Royal Montreal Regiment. It was a doctor with the RMR, not the Black Watch, who saved lives and later won the Victoria Cross when he advised soldiers to urinate in their socks and underwear (not their snot rags) to counter the effects of poison gas with uric acid. But that, perhaps, is more information than we need to know, and doesn’t alter the show’s underlying theme.

Motherhouse is not so much a play as an arresting diatribe in search of one. As the protagonist, Bradley, who worked at the British Munitions Factory in Verdun when her brother went off to fight the war, Holly Gauthier-Frankel has her work cut out for her. She is an enjoyably talented, energetic actor who does her best to get the audience involved. She leads sing-songs, unleashes her wry, self-controlled anger and keeps us engaged even when the script turns into an awkward and sometimes incoherent polemic. It’s a strenuous part and Gauthier-Frankel occasionally seems flummoxed by the demands of playing a century old-character. In fact a 1916 photograph of female factory workers on their lunch break inspired Fennario to write the play. Motherhouse touches on the linguistic and religious issues, conscription, and labor strife which divided the country during the war. Anyone who took Fennario’s walking tours through Old Montreal knows that the playwright, now confined to a wheel chair with Guillain-Baree syndrome, isn’t one to let the facts get in the way of his searing, anti-capitalist, left-wing rants. And Motherhouse is no exception. For example, he occasionally confuses the Black Watch with the Royal Montreal Regiment. It was a doctor with the RMR, not the Black Watch, who saved lives and later won the Victoria Cross when he advised soldiers to urinate in their socks and underwear (not their snot rags) to counter the effects of poison gas with uric acid. But that, perhaps, is more information than we need to know, and doesn’t alter the show’s underlying theme.

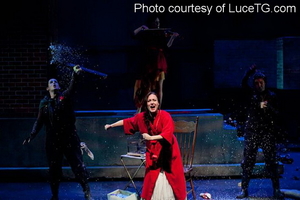

The production is reminiscent of Joan Littlewood’s empire-bashing O What a Lovely War, which used farce and music hall bombast to debunk the war’s blind patriotism and the pretensions of heroic sacrifice. Fennario’s message is unmistakable. In delivering it Gauthier-Frankel manages to walk a fine line between bravado, outrage, and poignant reflection. Especially moving is her account of the death of her brother who goes “missing in action.” She relies on the sheer force of her personality to galvanize the audience into paying attention. Three other performers, Bernadette Fortin, Stephanie McKenna and Delphine Bienvenu are, for the most part, a silent chorus, who help set the scenes, fill in the blanks of the narrative and provide the musical accompaniment even if it means banging on pots.

Laurence Mongeau’s lumbering grey set in turn variously serves as a church, a cenotaph, and even as Vimy Ridge, where toy soldiers ride a conveyor belt to their death. Lighting by Peter Spike Lyne enhances the melancholy atmosphere. Inexplicably, director Jeremy Taylor keeps Gauthhier-Frankel at centre stage throughout most of the raggedly paced show and relies on his theatrical inventiveness and multi-media techniques to augment her admirable performance and bring the text to life.

Commentaires

Veuillez vous connecter pour poster des commentaires.